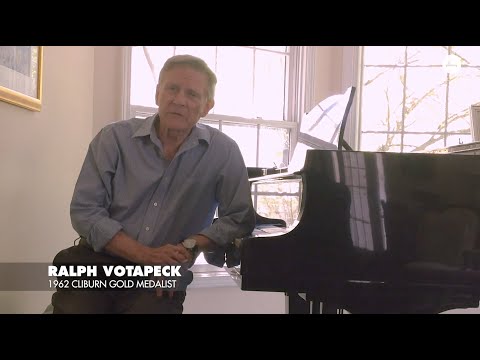

In the latest installment of our occasional conversations with Fort Worth newsmakers, the winner of the first Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 1962, Ralph Votapek, spoke with arts and culture editor Marcheta Fornoff about how the competition changed his life. In addition to playing solo recitals across the globe and performing with numerous orchestras, Votapek also served as artist-in-residence at Michigan State University for more than 30 years and was eventually named professor emeritus of piano in the school’s College of Music.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity. To hear more, please listen to the audio file attached to this article.

Fornoff: The structure of the competition has changed quite a bit from the very first one. I’m curious what you think of the additions and changes like the Mozart concerto?

Votapek: I think it’s a very good idea. I mean, it’s always been even from the first, it felt more like a concert with the audience. In fact, back 60 years ago, there were requirements, but as far as I remember… (I was) never stopped by a judge saying, “Could you proceed to this or could you cut this?” I’ve been in many competitions before (like) that, and I found them very nerve-wracking. And the Cliburn, I thought, was more like a concert.

We all had to play a Bach prelude fugue. And we all played a Beethoven sonata, and we all had to play a MacDowell sonata because that was Van Cliburn’s mother’s favorite composer, but the judges never heard it. In other words, the auditions were shorter. There was just a preliminary, semifinal and the concertos. There was not nearly as much playing as there is in today’s competition.

It benefits the contestants that, in a sense, it’s more stringent for them because they have to prepare a lot more repertoire. That’s the way it is in the concert world. You can’t just get by on a small repertoire or your career will be very short, I’m sure.

Fornoff: What made you interested in signing up for this very first round of the competition, not knowing what it would become or what the reputation might be? What made you certain that you had to do it?

Votapek: I entered everything I could at that time. I entered the Naumburg for the first time and won. I entered another competition three times, and each time I got further on, but I never won.

I came from a family that wasn’t musical. The only way I knew I could possibly make a concert career was by winning a major competition.

The thing that made the Cliburn attractive from the beginning was that we knew that the Russians were coming over.

Fornoff: And at the time, were you excited because they were known for being the best of the best, and this was your chance to compete shoulder to shoulder?

Votapek: It was well known that, in Russia, if you wanted to compete internationally, you had to compete internally and then they would permit you to come if they knew you were of high caliber.

In the Soviet (Union it) was all very regimented. From a very early age, if they knew you had talent, you went to a special school and then to another school and then eventually to the Moscow Conservatory.

I mean, that’s what made Van Cliburn’s victory so unprecedented, so surprising.

The fact that the Russians came over to this country in 1962 made the competition not just another competition.

…

Anyway, there’s another anecdote I’ve told many times, but one week before the competition, I was drafted into the U.S. Army.

I was given a one month’s notice to report to the Army for two years, so I went down to Fort Worth thinking, maybe I’ll make a little money and then I’ll go into the Army. I never realized that winning the competition, defeating the two Russians, would get me a year’s deferment from the Army. And that’s exactly what happened.

I was told by my host family not to tell that to anybody, because that could influence the jury. Why give the prize for somebody who’s going to go into the Army? Anyway, a few minutes after I got the gold spittoons, this gold champagne cooler, I said, “Well, you know, I’ll take the money, and I’m very appreciative, but I’m afraid I can’t take advantage of the concerts because I have to go to the Army next week. I was given one month’s notice that I was to report one week after the competition.” And Grace Ward Langford said in her Texas drawl, “Well, we’ll see about that, honey.”

And she called Gov. Connally, who called my local draft board. I had to report to the local draft board and give them the story that if I went into the Army, the prize would have to be awarded to the Russians. This was one week before the Cuban Missile Crisis. How’s that for luck?

Shortly after one year, I got married and they were no longer drafting married men. This was before Vietnam, so I mean, I wasn’t a conscientious objector. If (the answer was) go, I wasn’t happy about it, but I knew I had to go. So anyway, that’s the story about being in the right place at the right time.

Fornoff: Well, I was going to ask you about how the competition changed your life. And that’s one answer…

Votapek: That’s the answer. Yeah. It probably changed my life more than almost any other competition winner.

Fornoff: You said you didn’t have any advice for the current competitors…

Votapek: No. They all seem brilliant. They all seem very musical and their repertoire choices are very interesting.

I was on the jury twice in the Cliburn in ’89, in ’93. Sometimes people would say, “Oh, how in the world (do) you decide who’s the best?” And I simply said, “The one that I like the best.” It seemed easier at that time. In other words, still in that time it seemed there were people who played well, but not that well, and so it is easier to discern who would be the six finalists. After that? Then it’s a kind of a crapshoot.

But now you’ve got 30 contestants. I’ve only heard snippets of some and large portions of others. But it might be a little harder to tell because they all seem so, so good. I mean, they don’t miss. I mean, there’s no such thing as memory slips, it seems. Maybe I’m wrong, but anyway, it’s kind of inspiring.

Fornoff: I know you said you don’t have advice for the competitors this year, but I’m wondering if you have advice for people who might be considering applying to the Cliburn in the future?

Votapek: Well, that’s a tough question. I just always remember Isaac Stern, the famous violinist. He says the secret to a long career is you enjoy your playing. And if you can’t play for audiences, then enjoy playing for yourself or for your friends.

Anyway, good luck to the Cliburn. They’re doing a wonderful thing.

Marcheta Fornoff covers the arts for the Fort Worth Report. Contact her at marcheta.fornoff@fortworthreport.org or on Twitter. At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.